We See Us as We Want to See Us

On Creativity, Confidence, and Coming Back to Yourself (in my new class on creativity)

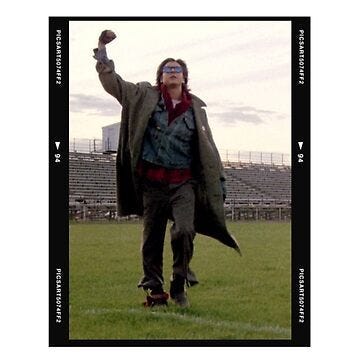

We all remember it. John Bender, 1985.

Walking alone across an empty football field in a denim jacket and fingerless gloves. Wind in his hair. Bruises on his ego. The school day is over. Detention is done. E.g.:John Bender, 1985. The Breakfast Club.

And just before the credits roll, he throws a fist into the air.

No applause. There is no soundtrack swelling. No one was there to see it.

Just Bender, claiming a small, silent moment of defiance. A personal win.

Most of us watched it unfold from the safety of our lounge rooms — on VHS tapes, on after-school reruns! But in that frame, no one’s watching him. That was the point. He was walking alone.

It wasn’t a performance. It was a release. A declaration to no one and everyone at once.

And maybe that’s what makes it stick. It wasn’t about being seen. It was about finally seeing yourself.

We all wanted to be Bender once. Not just because he was cool (though he was) but because he did something bold without waiting for approval. He broke the rules, stood his ground, and walked off like it meant something.

And still — if we’re honest — we all hoped someone was watching.

Because there’s a strange kind of ache comes with doing something remarkable when no one sees it. Especially if you’re not trying to be impressive underneath it all — we're just trying to feel connected.

Fourteen years ago, I flew to the Gold Coast to speak at the Energy Asia Pacific Conference. Back then, many of my clients were fossil fuel giants and legacy brands — names we no longer work with today. (As a B Corp, our priorities have changed. Dramatically. So when I mention them, I do so knowing we have turned the page on Fossil fuel giants)

The morning before my talk, I found myself with a bit of time to kill. The venue was a golf resort, so I grabbed a set of clubs and headed out alone for a quiet nine holes. No pressure. No crowd. Just me and a battered swing. I was crap. Useless in fact!

Or was I? On the fourth hole — a short par three — I hit a shot that felt… different. Clean. Smooth. Like it had a destination before it even left the club face.

I didn’t watch it land properly (I rarely do, its often a road or a carpark), but this felt good, so I just walked toward the green thinking, I know this one landed on the green.

Then I noticed something: no ball. Not on the green, not in the rough, not in the trap.

Eventually — almost sheepishly — I looked into the hole.

And there it was.

A hole-in-one.

I stood there for a moment, waiting for the rush. The adrenaline. The high-five-from-the-universe kind of feeling.

But instead, I felt… still. Joyful, yes. But also strangely alone.

Because a hole-in-one is meant to be a shared experience. The beers. The storytelling. The handshakes. The retelling in slow motion.

But when it’s just you? No one to witness it? It becomes something else entirely.

Not meaningless. Just… quieter.

That moment stayed with me.

The day before, I’d played a round of golf with friends. Sure, I was crap — but what made it great wasn’t the golf. It was the people. The laughs. The feeling that we were all a little out of our depth, but playing anyway.

Creativity is like that. It’s rarely about the perfect shot — it’s about the moment, the connection, the people you get to share it with.

And somewhere along the way, I’d lost that.

Between 2010 and 2018, I gave keynote speeches (so many), spoke at conferences (way to many), and participated in workshops. At one point, I was being paid up to five figures to talk for 30 minutes, and for a while, I felt like I had a lot to say.

I spoke at Vivid Sydney, Tedx, Parliament House to the Prime Minister, Creative Sydney, Design events in LA, London, Queenstown, Hamilton, Fiji, Bali, BHP Billiton, Caltex, and Elgas, worked with Gulf Oil and Unigas, and gave talks at the Energy Asia Pacific Conference, where the rooms were packed and the slides polished.

I had momentum. But I didn’t realise I was also drifting. Slowly. Quietly. Away from what mattered.

And looking back, I see it wasn’t that I stopped being good. I stopped being me. Other people's opinions, feedback, and criticism changed how I spoke and what I decided to speak about.

One of the golden rules of public speaking is to make eye contact. Find someone in the crowd, connect, and rotate — standard stuff.

So, during a talk at a Caltex conference in Melbourne, I picked a guy. Mid-fifties, sitting near the front. Every time I looked at him, he’d shift in his seat. Look away. Then, partway through the talk, he started shaking his head — subtly at first, then more… energetically.

I couldn’t tell if he hated what I was saying or was reacting to something internal — bad lunch, maybe? But it rattled me. I kept trying to find other faces to lock onto but kept returning to him, like some awkward, unspoken duel.

That night at the function, I saw him again. He was talking to people I knew, so I walked over.

“Hey, mate,” I said, half-joking. “Didn’t mean to ruin your day up there.”

He looked confused. “What are you talking about?”

“You were shaking your head through my whole talk.”

He laughed. “I loved your talk. I couldn’t understand why you kept staring at me.”

It turns out that the entire time I thought he was silently judging me, he thought I was doing the same to him. We were locked in a loop of mutual discomfort. Both convinced the other was the villain in the scene.

At a different event — one of the biggest cereal companies on the planet — I gave what I thought was a pretty solid talk. I spoke about innovation and the importance of vulnerability in leadership. I referenced a few books I’d been reading at the time: one by Brené Brown, another by a female author, and another… also by a woman.

Afterwards, in the Q&A, a woman marched up to me and said, “Your talk was incredibly sexist.”

I blinked. “Sorry, what?”

“You only mentioned female authors. That’s biased.”

I realised something fundamental about speaking: it’s not just what you say — it’s what people hear. And what they hear is filtered through everything they bring into the room.

Like in high school, people hear what they need to hear, not always what you intended to say.

Then, a young man made a beeline for me at a City of Sydney talk. No hello. No handshake. Just:

“That was boring. I’ve heard you say all that before.”

It stung. Because it was true.

That guy's energy impacted mine, convincing me to change my TEDx talk the night before I gave it. I scrapped the talk I cared about and replaced it with something I barely understood.

And it bombed.

It was the first time I truly felt like I was faking it. I was performing a version of myself rather than the one I knew.

And when that happens — when you stop listening to your voice and start chasing approval — it doesn’t matter how many people are clapping. It won’t land.

So in 2018, I stopped. I walked away from speaking engagements—the stages, the lights, the rehearsed hand gestures. I stopped not because I hated them but because I didn’t know what I wanted to talk about.

It was like Bender walking out of detention and realising he wasn’t sure if he was still the criminal or just playing the role expected of him.

I’d been performing. And I was tired of performing.

In my book Lessons in Creativity, I detail how I left my own business and started again in 2018—back to stage one, from scratch, based on the intention to build a new company with a clear purpose. It was terrifying but also necessary.

And somewhere in that reset, I started writing a book on creativity.

When you spend three years digging through research papers, data points and the philosophy and psychology around what creativity is, how it works, and why we lose it, you start to see things differently. You begin to see yourself differently.

The data hit hard. 96% of children believe they’re creative. Whereas only 26% of adults do. By age 50, it drops to 3%.

Three. Per cent.

That number hit me.

Not as a stat, but as a mirror.

Because I’ve felt that drift. The slow fading. The moment you realise you’re no longer creating from instinct — you’re performing from memory.

And I started to wonder: what if we haven’t lost creativity at all? What if we just stopped listening to it? Or, more so, choosing it!

That’s what I care about now. Not being seen. Not sounding impressive. But helping people reconnect with something they didn’t lose — just misplaced.

Not by giving them a how-to list. But by sharing what I’ve learned — through research, stories, missteps, and moments that didn’t land the way I thought they would.

That’s why I’m speaking again. Not about innovation. Not about trends or tactics. But about creativity. The real stuff. The quiet stuff. The space between who we are and who we hoped we’d become.

Last year, I ran a few workshops. Small groups, open discussions. No hype, just space to think, talk, and unpack the creative process. Every session sold out. So, I’m doing more.

This one’s called Closing the Creativity Gap.

It’s designed for people who once saw themselves as creative — and aren’t sure if they still are. Or maybe they’re just wondering where that spark went, and what might bring it back.

You’ll get a signed copy of Lessons in Creativity, a fold-out Creativity Manifesto, and we’ll finish with a live Q&A — open, unscripted, and honest. Nothing polished. Just real questions and real conversation.

If this resonates, you can find details about the next workshop here.

As Sir Ken Robinson once said, creativity isn’t something you have or don’t have — it’s something you build.

So here I am. Rebuilding. Speaking again — not to be seen, but to connect. To say something that matters, even if there’s no applause at the end.

Because sometimes the real win isn’t the standing ovation. It’s the quiet fist in the air when no one’s watching.

That’s how you know it mattered.