Vinyl Revolutions: Let the Records Play (and how our past shapes our future)

It’s 1985, and I’m sitting in our sunken lounge room at the foot of the Blue Mountains. The thick shag carpet cushions my feet, and the…

It’s 1985, and I’m sitting in our sunken lounge room at the foot of the Blue Mountains. The thick shag carpet cushions my feet, and the faux brick walls radiate a kind of warmth that only those who lived it would understand. In front of me sits the vinyl record player — a grounding presence in an era before technology became disposable. I picked up the album 1985 Comes Alive, sliding the record carefully from its sleeve. There’s a weight to the action, a deliberate slowness. I brush off the dust, set it on the turntable, and lower the needle. I’m only 10, but the following crackle is familiar, even comforting. It still is today. Soon, the music filled the room, but it was more than sound — it was an experience I could still recall like yesterday, vivid and full of meaning.

Playing a vinyl record demands attention. It’s a ritual, deliberate and unhurried. And in that slowness, something significant happens — you become part of it. You slow down, immerse yourself, and in that moment, you make space for something often missing — creativity.

There’s a certain romance in the rituals we remember — the act of touching (things), feeling (emotions), and choosing (what connects). We connect to our creative instincts in the slowness and deliberate engagement with the world. When we’re present, free from the endless pings and notifications, our minds have the space to wander, to make unexpected connections, and to create. Analogue moments — where we handle, listen, and experience — ignite something more profound. But today, we’ve traded that deliberate pace for speed and convenience. In doing so, we’ve lost something irreplaceable: the space where creativity thrives.

Consider how we consume entertainment today: endless scrolling through streaming services, bombarded with choices. If a film doesn’t grab us in the first five minutes, we move on without a second thought (please tell me that it is not just me). It’s seamless — but it’s also detached. Now, think back to the experience of going to Blockbuster or Video Ezy. It wasn’t just about the movie — it was about the entire ritual. Getting in the car, wandering the aisles, debating what to rent. That process, that journey, built anticipation. When you brought the movie home, it wasn’t just something to watch — it was an event, something you were fully invested in.

Sure, streaming gives us time back — but how are we using that time? Going out, engaging in the process, and sharing in anticipation created moments of excitement, a space where creativity naturally thrives. Now, with everything available at the tap of a button, we have more time but less depth.

Creativity thrives on space, time, and authentic engagement — elements that have been sacrificed for convenience. The analogue world allowed creative thought to grow by forcing us to slow down. When everything arrives instantly, that vital space for creativity and the depth of our ideas shrinks.

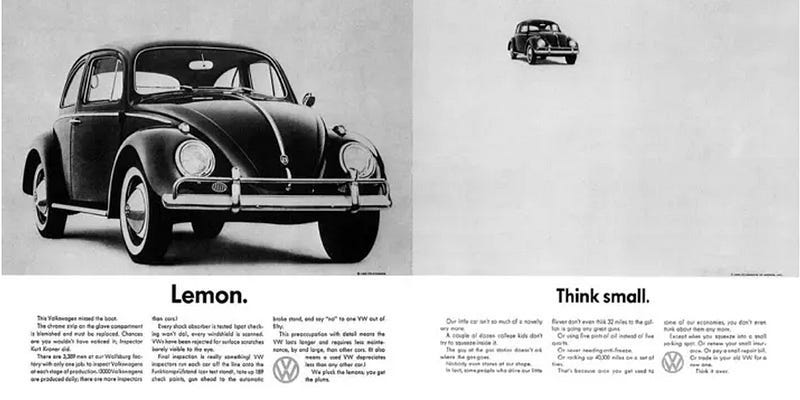

Looking back at the creative pioneers of the past, we can learn something critical about the value of process and disruption. Bill Bernbach and Paul Rand weren’t just figures in advertising and design; they were architects of a creative revolution that fundamentally changed how we think about creativity in business. In the 1940s, the creative process in advertising needed to be more cohesive and mechanical. Copywriters and designers worked in silos, each confined to their roles, handing off their work in a kind of creative assembly line. Words and images were separate worlds. The writer wrote, the artist designed, and rarely did the two meet.

But when Bernbach met Rand, something shifted. They didn’t just see words and visuals as components of a message; they understood that they were inseparable. Their collaboration broke down the walls between design and copy, fusing them into a cohesive process where ideas flowed freely between language and image. Creativity was no longer about isolated, clever lines or visually striking designs — it was about creating holistic ideas that resonated on a deeper level. They saw creativity as something that couldn’t be compartmentalised. It needed to be nurtured, explored, and integrated into every part of a brand’s DNA.

Their work and way of thinking made Bernbach and Rand game-changers. Bernbach, as a copywriter, challenged the rigidity of the advertising industry. He believed that advertising could be more than just a mechanical means of persuasion. His famous quote, “An idea can turn to dust or magic, depending on the talent that rubs against it,” captures his core belief that creativity was about collaboration and human insight, not just process. He saw the potential in words, but he knew that the magic happened when they worked hand in hand with design. He understood that people didn’t buy products — they bought feelings, stories, experiences.

Rand took this philosophy and ran with it. He didn’t just make things look good; he solved problems through design. When he left Madison Avenue in 1954, frustrated with the limitations of the traditional agency model, he didn’t simply set out to make logos or ads — he set out to redefine what design meant in the corporate world. His work with IBM, Westinghouse, UPS, and other significant corporations was about more than aesthetics. He embedded creativity into the very fabric of these companies, helping them articulate who they were, not just what they sold. His designs were timeless, flexible, and driven by a deep understanding of how design could shape perception, build trust, and drive innovation.

Rand didn’t just design logos — he created entire systems of identity that could evolve with the company, systems rooted in problem-solving. He believed that design was as much about function as it was about form and that excellent design didn’t just communicate — it built brands from the ground up. His work proved that creativity wasn’t just an afterthought or embellishment but a strategic asset.

Together, Bernbach and Rand shifted the entire paradigm of advertising and design. They clarified that creativity couldn’t be split into departments or reduced to a step in the process. It was a way of thinking, a force that could transform not just a brand’s image but its very identity. They showed us that creativity can shape industries, change narratives, and connect people in profound and lasting ways when fully integrated and allowed to flow freely.

This is why they matter. They didn’t just produce iconic work — they redefined the rules of creativity, showing us that the best ideas don’t come from isolated efforts but from collaboration, integration, and a deep understanding of creativity’s human and business sides. Their legacy reminds us that creativity is not a luxury — it’s essential to solving problems, telling stories, and moving industries forward.

The message is clear: creativity isn’t a department. It’s not something you can box up, delegate, and then move on while the rest of the organisation does the ‘real’ work. Creativity is everywhere — how we approach problems, think about the future, and adapt to change. Just like the analogue world, creativity demands time. We must slow down, engage fully, and immerse ourselves in the process.

Yet we lost that understanding somewhere along the way, especially in tech-driven corporate sectors. Creativity became a commodity to be called upon when convenient and outsourced to a select group. We split it off, labelled it as a function for the ‘creatives,’ and expected them to deliver while the rest of the business carried on. But that’s not how creativity works — it can’t be compartmentalised.

As I reflect on how creativity is nurtured — or rather, stifled — in modern life, I keep returning to the idea of the “Creativity Gap.” It’s the gap between the 96% of children who believe they are creative and the 26% of adults who feel the same. Somewhere along the way, creativity is lost or, at the very least, forgotten. This gap has reshaped my thinking about design, especially Human-Centred Design, which feels increasingly inadequate in today’s complex world.

Human-centred design, for all its intentions, has become too narrow. It focuses on solving immediate, often isolated problems but needs to account for the larger, interconnected systems we live in today. We’re facing challenges that can’t be solved by thinking in silos — challenges like reversing the damage from single-use plastics, tackling the climate emergency, rethinking our political systems, or even rebuilding trust in democracy and language. These are problems that don’t just need better solutions — they need interwoven, adaptive, and systemic solutions.

This is where my Systemic Design Foundations approach reimagines what design can do in a world that demands deeper, more holistic thinking. Systemic design isn’t about quick fixes or surface-level innovation. It’s about understanding that the solutions to our biggest challenges require us to think across systems, see the ripple effects of every decision, and connect the dots in ways that traditional design frameworks simply can’t.

For decades, designers have battled with what Ralph Caplan so aptly described as the role of the “exotic menial.” Coined in 1981, Caplan pointed out that despite their creativity, designers were often relegated to roles where their work was seen as secondary, even ornamental, only called upon to style or package a decision already made. And the worst part? Designers often colluded with this arrangement. They became exotic, mysterious, but menial — offering surface-level solutions to deep-rooted problems.

Forty years later, a lot has stayed the same. Too often, creativity is misunderstood as mere decoration, especially in corporate environments where strategic thinking and ‘real business decisions’ are held at arm’s length from the creative process. As a result, the role of design has been diminished, and its power to drive meaningful change has been overlooked in favour of short-term wins and aesthetic flourishes.

But here’s where Systemic Design offers a necessary disruption. It challenges this outdated mindset and places creativity at the heart of problem-solving, not just as an afterthought. The power of Systemic Design is in its ability to transcend the “exotic menial” role and instead focus on the bigger picture — addressing complex challenges like climate change, single-use plastics, and political systems. These problems cannot be solved with a slick logo or a catchy tagline. They require more profound, more integrated thinking, something that Caplan’s critique laid the groundwork for.

Design’s power isn’t in making things look good — it’s in making things work better. This is the shift that the next creative revolution is already starting to see: from exotic menial to essential collaborator. And it’s not coming from massive corporations or siloed departments; it’s coming from small, agile teams and individuals who understand that design, when treated as a force for systemic change, can drive meaningful, long-lasting solutions.

Caplan’s words still resonate today. Good design isn’t just about aesthetics — it’s about creating systems that work for people, businesses, and the planet. It’s about rethinking the designer’s role, not as an accessory to strategy but as a critical player in shaping it. In this world where design can no longer afford to be relegated to the sidelines, those who embrace this shift lead the charge into the next creative era.

We need this mindset now more than ever. As we face global challenges requiring complex, nuanced solutions, we must embrace systemic thinking and creativity as the keys to solving them. The creativity gap isn’t just a problem of identity — it’s a gap in how we approach solving the world’s most pressing issues. If we can close that gap — if we can reawaken creativity in ourselves and others — we have the power to build innovative and lasting systems, communities, and solutions.

How do we reclaim creativity in a world of speed and instant access? It starts with something simple — slowing down. We need to carve out space to fully engage with whatever we’re doing, whether playing a record, designing a product, or tackling a complex challenge. Creativity flourishes when there’s freedom to take risks, fail, and start again. It’s not a straight line — it’s an evolving loop that needs time and room to grow.

This isn’t about rejecting the digital age. It’s about balance — embracing the speed and efficiency of technology while preserving the slower, more intentional processes that analogue taught us. In that balance, creativity finds its full power — not just in speed, but in depth.

Today’s fundamental shift is that power has moved away from massive corporations and siloed agencies. The next creative revolution will come from small, agile teams and individuals who understand how to adapt and evolve. These people know that creativity isn’t confined to departments — it’s a force that flows through everything they do. They’re not waiting for permission. They’re acting, solving real-world problems, and reshaping the future by thinking differently.

As the world changes, so does our relationship with creativity. The power has shifted. By blending past lessons with today’s tools, we can shape a future where creativity is not just something we do — it’s something we are.